As part of the ongoing series ‘Judges of Death,’ this report focuses on Abolqasem Salavati, head of Branch 15 of the Revolutionary Court in Tehran (a special court under Iran’s Revolutionary Judiciary). His name has become synonymous with heavy sentences, coerced confessions, and politically driven trials targeting protesters, political prisoners, and members of religious minorities. Rather than listing victims, this report analyzes the structural pattern of his conduct: the systematic denial of fair trial guarantees, elimination of the right to defense, and transformation of the court into an instrument of political repression. Salavati has consistently acted as an operative of Iran’s security agencies, rather than as an independent judge.

Fair Trial Violations and Show Trials

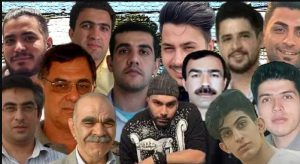

Salavati’s judicial record represents the collapse of due process in Iran’s legal system. Data from international human rights organizations, including United for Iran and the Atlas of Iranian Prisons, show that by 2020 he had issued at least 25 death sentences and more than a thousand years of prison terms for hundreds of defendants. Dozens were denied access to lawyers of their choice. Trials under his authority were short, closed-door sessions in which defendants were not allowed to review their files or present evidence. The judge routinely repeated interrogators’ narratives in his verdicts, converting the courtroom into an extension of the interrogation chamber. Confessions extracted under torture were accepted as conclusive proof.

Mass Death Sentences and Political Executions

Salavati’s approach to justice reflects the regime’s broader policy of eliminating dissent through legal violence. Over the past two decades, he has issued mass death sentences against protesters and political prisoners. During the 2022 nationwide protests, he sentenced Mohammad Broghani and Mohammad Ghobadlou to death; Ghobadlou was executed in February 2024 in Qezel Hesar Prison, while Broghani’s case remains pending. He also sentenced Mohsen Shekari, the first protester executed after the 2022 uprising. In the November 2019 protests, Salavati sentenced three young demonstrators—Amirhossein Moradi, Saeed Tamjidi, and Mohammad Rajabi—to death, later reduced to five years in prison after public outrage.

Salavati previously issued death sentences for Kurdish political prisoners Farzad Kamangar, Farhad Vakili, Shirin Alam-Holi, Zaniar and Loghman Moradi, and three supporters of the People’s Mojahedin Organization of Iran—Ali Saremi, Mohammad-Ali Haji-Aghaei, and Jafar Kazemi—who were executed in 2010. He also presided over the cases of journalist Ruhollah Zam, nuclear case defendant Majid Jamali Fashi, and Quran interpreter Mohsen Amir-Aslani, all of whom were executed following unfair trials. The same judge has handed long prison terms to six environmental activists and recommended capital punishment for several others under charges of ‘enmity against God’ and ‘disturbing national security.’ These cases demonstrate the systematic use of capital punishment as a political tool of intimidation.

Religious and Intellectual Persecution

Religious and Intellectual Persecution

Salavati has used his position to criminalize belief and thought. Branch 15 of the Revolutionary Court has become a center for persecuting members of the Bahá’í community, Gonabadi dervishes, and independent thinkers. Among those he sentenced were Bahá’í educators Farán Hesami, Kámrán Rahimian, and Keyván Rahimian, who were imprisoned for teaching at the Bahá’í Institute for Higher Education. In July 2013, he sentenced seven Gonabadi dervish lawyers and activists, including Hamidreza Moradi Sarvestani, Reza Entesari, and Mostafa Daneshjoo, to over fifty years in prison. Likewise, he imprisoned physics PhD student Omid Kokabi for refusing to collaborate on military projects, and executed Mohsen Amir-Aslani for expressing unorthodox religious views. These actions violate Article 18 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which guarantees freedom of religion and belief.

Judicial Corruption and Witness Accounts

Reports describe Salavati as deeply entangled in corruption and fully protected by Iran’s security apparatus. Complaints against him within the judiciary are routinely dismissed, and those who criticize him often face threats or prosecution. This impunity has allowed him to use his position for personal and political gain while maintaining a façade of judicial authority.

Witness accounts also reveal patterns of coercion and intimidation during interrogations and trials. According to one acquaintance, Salavati once admitted that he had used every possible method to extract a confession from a detainee: ‘I tried everything to make him talk. When he still refused, I brought his family from another city late at night and put them under pressure until he finally confessed.’ This account shows that, for Salavati, intimidation and psychological coercion—even involving family members—were normalized as part of the judicial process. It illustrates the deeply embedded culture of coercion and systemic violence that defines Iran’s judiciary under his authority.

International Sanctions and Global Reactions

Abolqasem Salavati is under international sanctions for gross human rights violations. The European Union first sanctioned him in April 2011 for his role in post-election show trials in 2009, imposing a travel ban and asset freeze. The U.S. Department of the Treasury sanctioned him in December 2019 under Executive Order 13846, citing his responsibility for politically motivated executions and denial of due process. Canada followed in June 2023, coordinating with the EU and U.S., and the United Kingdom added his name to its Global Human Rights Sanctions list the same year.

United Nations human rights mechanisms have repeatedly identified Salavati as one of Iran’s leading judicial perpetrators of arbitrary deprivation of life. UN Special Rapporteur Javaid Rehman and other experts have documented his systematic violations of fair trial guarantees. Amnesty International and the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) have called for his prosecution under the principle of universal jurisdiction. The consistency of these sanctions demonstrates a clear international consensus that Iran’s judiciary, as represented by figures like Salavati, operates as an instrument of state repression rather than a guarantor of justice.

Conclusion and Call to Action

Abolqasem Salavati’s record embodies a judiciary that serves power, not justice. From denying defendants access to lawyers to imposing death sentences based on coerced confessions, his actions demonstrate a deliberate policy of judicial terror. His protection within the judiciary, despite overwhelming evidence of abuse, illustrates the culture of impunity entrenched in Iran’s legal system.

To break this cycle of impunity, it is essential that international bodies, human rights organizations, and national courts invoke universal jurisdiction to investigate and prosecute Salavati and others responsible for these crimes. The report calls on the United Nations Human Rights Council, European institutions, and national courts to ensure that such judicial crimes are not left unanswered.