High number of Iran executions in 2021 signals worsening rights condition

October 10 is World Day Against the Death Penalty. More than 140 countries have agreed to abolish the death penalty, according to Amnesty International. The Iranian regime, however, holds the world record for both executions of women and the highest per capita execution rate.

The death penalty is a violation of Articles 3 and 5 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which emphasize the right to life of every human being.

It is also contrary to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

The Iranian regime continues to use the death penalty as a tool to intimidate and repress dissidents; And many regime officials also defend it.

In his first news conference after the June 2021 election, the regime’s president Ebrahim Raisi, who is responsible for the massacre of political prisoners in 1988 and other crimes against humanity, defends himself over the executions and said that he should be rewarded for defending people’s rights and security.

Gholam Hossein Mohseni Ejei, the current head of the regime’s judiciary, who was appointed to the post by Khamenei on July 1, has also a dark record regarding the execution of dissidents in Iran.

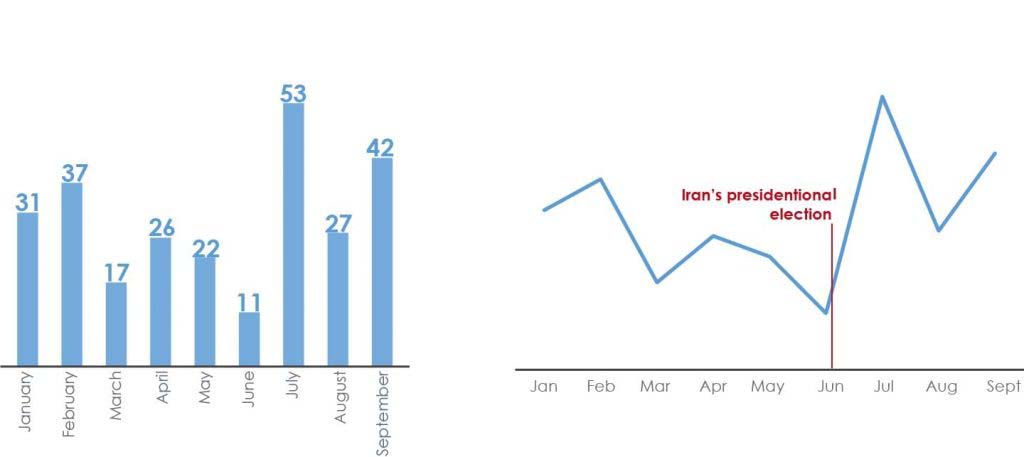

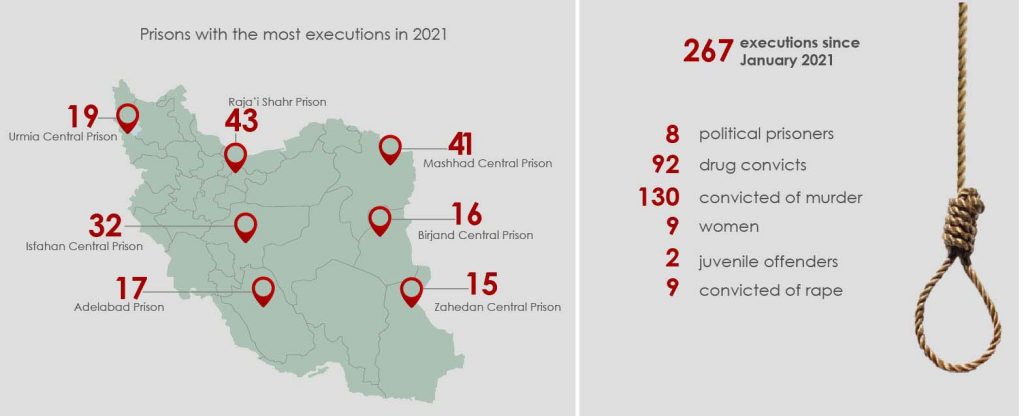

According to statistics compiled by Iran Human Rights Monitor, at least 267 people were executed in Iran since the beginning of 2021.

Iran executions in 2021

This shows an increase over the last year, when 255 people were executed throughout 2020.

The actual number of executions is much higher. The clerical regime carries out most executions in secret and out of the public eye. No witnesses are present at the time of execution but those who carry them out.

At least 92 executions were carried out for drug-related offenses in 2021 and 130 were carried out for murder. Nine women, eight political prisoners and two child offenders are among those executed.

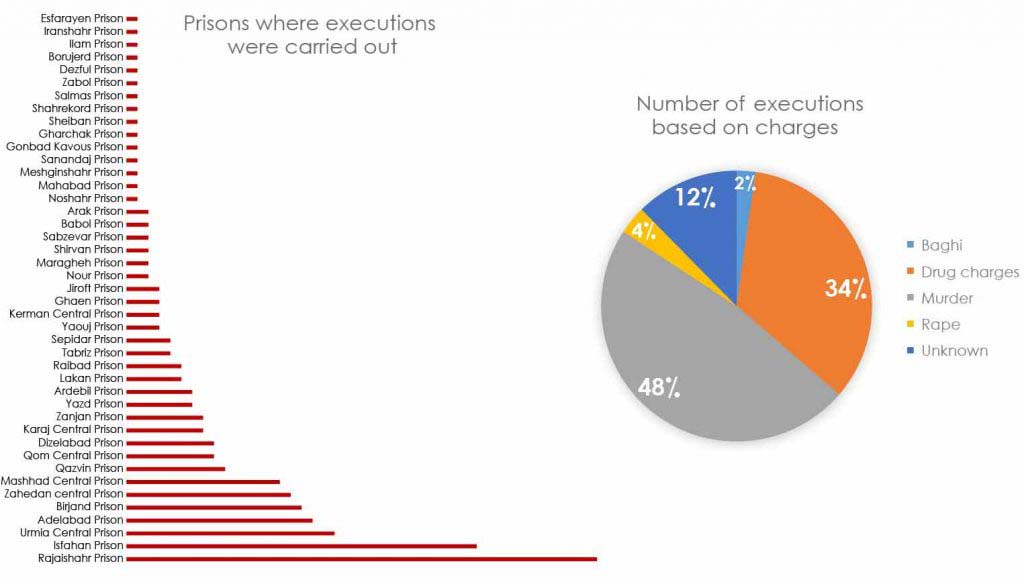

Prisons where executions were carried out since January 2021

The high number of Iran executions in 2021 once again proved that the clerical regime uses the executions as a mean to its survival.

There is irrefutable evidence that torturing defendants for making false confessions against themselves is a common practice in Iran’s prisons.

On the World Day against the Death Penalty, Iran Human Rights Monitor once again calls on the UN Secretary-General, the Human Rights Council and the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, as well as European countries, to take immediate action to save the lives of prisoners on death row in Iran. It is time for Iran’s human rights record to be referred to the UN Security Council.

Execution of juvenile offenders in 2021

Iranian authorities have continued to execute child offenders in violation of their international obligations. Since January, at least two child offenders were executed in Iran. Dozens of juvenile offenders in prisons are also currently at risk of execution.

UN rights chief Michelle Bachelet in June pointed to Iran’s “widespread use of the death penalty” and said that “over 80 child offenders are on death row, with at least four at risk of imminent execution”.

Responding to the criticism Majid Tafreshi a senior Iranian official said that the death penalty for crimes committed as minors does not mean it violates human rights. Tafreshi, the council’s deputy head of international affairs argued that executes convicts for crimes they committed while under-age “three to four times” a year.

Execution of women

At least nine women were executed in Iran since January 2021. The clerical regime in Iran is the world’s chief executioner of women. The regime frequently hands down the death penalty for women.

The international law recommends alternative punishments for the imprisonment of mothers who must take care of their children. In Iran, however, the regime imprisons mothers and hands down death sentences for them.

In an infamous example of the death penalty for women Zahra Esmaili, 42, who died of a heart attack while waiting to be executed was still hanged on February 17, 2021. She was sentenced to death for having claiming responsibility for the murder of her husband who was a senior official in the Ministry of Intelligence. She did so to save her teenage daughter, who had shot her father in the head. According to her lawyer, she was made to watch as 16 men were hanged in front of her while waiting her turn at Rajai Shahr Prison, west of the capital Tehran.

Execution of political prisoners

Since January 2021, at least nine political prisoners were executed in Iran.

Hassan Dehwari and Elias Ghalandarzehi, two Sunni Muslim Baluch political prisoners were executed in Sistan and Baluchistan Province on January 3, 2021, for the charge of armed attacks on police and collaborating with opposition groups. They were tortured to make confessions.

Javid Dehghan, 31, a member of Iran’s Baluchi ethnic minority, was hanged on January 30, 2021. He was sentenced to death for “enmity against God” (moharebeh) in May 2017 in connection with his alleged membership in an armed group. In convicting and sentencing him to death, the court relied on torture-tainted “confessions” and ignored the serious due process abuses committed by Revolutionary Guards agents and prosecution authorities during the investigation process.

Ahwazi Arab prisoner Ali Motairi was on hunger strike when he was executed on 28 January 2021. He was also sentenced to death despite serious due process violations, including allegations of torture and forced “confessions”.

Hossein Silawi, Ali Khasraji, Naser Khafajian and Jassem Heidari were executed in secret in Sepidar prison on 28 February 2021.

At the time they had sewn their lips together and been on hunger strike since January 23, 2021, in Sheiban prison in Ahvaz, “in protest at their prison conditions, denial of family visits, and the ongoing threat of execution.”

Their relatives who saw their bodies after execution said that bruising was visible on all four men, raising concerns that they had been tortured or otherwise ill-treated, and their lips had not healed from when they sowed them shut on hunger strike.

Iran executed another Arab political activist, Ali Motiri on January 28, 2021 who had been accused of killing two members of the IRGC’s Basij militia in 2018.

Executions on rape charges

At least nine prisoners were executed on rape charges since the beginning of 2021. Under international law, countries that still use the death penalty must limit its use to the most serious crimes, namely premeditated murder. With the execution of those accused of rape, the Iranian regime continues to brutally violate the right to life in violation of its international obligations.

On 29 September, despite domestic and international interventions, Iranian officials executed Farhad Salehi Jabehdar, a 30-year-old man sentenced to death for the rape of a child. He was sentenced to death by Criminal Court One of Alborz Province on 12 March 2019. The conviction and sentence were upheld by the Supreme Court.

The father of the child formally requested that the authorities not impose the death penalty on Farhad Salehi Jabehdar in November 2019. His lawyer appealed to President Ebrahim Raisi in his former capacity as head of the judiciary to stop the execution, and order a review of the case, but Ebrahim Raisi did not accept the request.

Executions on drug charges

The use of the death penalty for drug charges is prohibited under international law. However, the Iranian regime continues to execute drug offenders.

In 2021, the number of executions was much higher than the previous year.

In 2020, at least 26 people were executed in various Iranian prisons for drug offenses. This is while the figure reached 91 in the first 9 months of this year.

Executions for murder

At least 130 prisoners were executed on murder since January 2021 in Iran. Many of them were executed in an unfair trial in Iran on murder charges. On several occasions, these detainees have been reportedly denied the right to a lawyer during the trial or have been tortured for forced confessions.

Two prisoners were executed in September based on Qassameh. Qassameh, which means “sworn oath”, is described as a certain number of people swearing an oath on the Quran. It is used when the judge decides that there is not enough evidence of guilt to prove the crime but still thinks it is likely that the defender is guilty. The people who swear in Qassameh are not usually direct witnesses to the crime.